The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties

Ian MacDonald

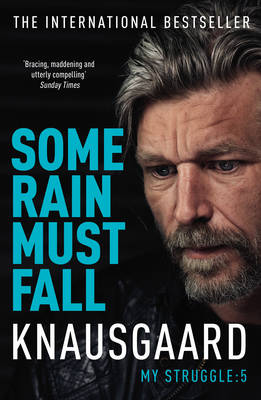

Revolution in the Head, first published in 1980, has been on my shelf for several years, so what led me to it now? I can’t tell you, but I knew it was mine. I didn’t want to read fiction, or Knausgaard, or psychiatry, or animal behavior, or any of my usual bollocks, so I picked this volume of Beatles songs analysis – a famous, famous pop music book – with a big odd shape and a psychedelic cover like a Beatles album or a Monty Python annual. I took it and collapsed on the kitchen sofa and went into a dream.

Revolution in the Head, first published in 1980, has been on my shelf for several years, so what led me to it now? I can’t tell you, but I knew it was mine. I didn’t want to read fiction, or Knausgaard, or psychiatry, or animal behavior, or any of my usual bollocks, so I picked this volume of Beatles songs analysis – a famous, famous pop music book – with a big odd shape and a psychedelic cover like a Beatles album or a Monty Python annual. I took it and collapsed on the kitchen sofa and went into a dream.

MacDonald’s writing is equal to the music. That’s Point One. He insists in the introduction that he will not prostrate himself, but then he charmingly admits that, yes, of course, he is a huge fan of the Beatles. Which won me over. And then he tells the story through the songs – and in a way that is just so interesting at every turn.

Paul McCartney’s songs generally reflected his cheerful personality, not only in the lyric but also in the melody, which MacDonald describes as “vertical” in its jumping up and down the scales. McCartney wrote great tunes. Lennon’s by contrast were “horizontal” – notes close together, sometimes a lot of the same note – reflecting his dislike of the cheap and easy. MacDonald makes the point that Lennon valued emotional truth over form (I thought of DH Lawrence). McCartney, however, under Lennon’s influence, wrote some gritty songs. We Can Work it Out was an early example. Getting Better was a later one – a song I’d always thought was Lennon’s.

McCartney was “the great multi-instrumentalist”, according to McDonald, not only one of the great bassists, but also a great guitarist and drummer and genius arranger. He was a far better musician than Lennon who (perhaps to his advantage) was actually a clumsy guitarist. Lennon was probably the greater artist, though, and abrasive and sardonic and endearingly silly. He was a big fan of Peter Sellars and Spike Milligan – he loved how they were sending up The Establishment. MacDonald is good both on George Harrison, the most complex Beatle, a mate of Bob Dylan, and on Ringo Starr, dispelling the myth that Starr was not a great drummer.

In any case, MacDonald views all the music that the individual Beatles made post-divorce as hugely inferior to what they made together. The creative power was in the relationships.

Abbey Road was my own introduction to The Beatles. Jonny Landau gave it to our family as a present around 1971 and it was the only Beatles record my parents ever owned. It was the only pop music they ever owned. Mostly they went for musicals, like Oklahoma, South Pacific, Guys and Dolls, West Side Story, Hair, Godspell, Jesus Christ Superstar, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, Cabaret, the soundtrack from The Sting, and Chicago and Evita, not to mention South African musicals like King Kong and Ipi Tombi, or else for singers like Frank Sinatra (especially) or Louis Armstrong or Harry Belafonte.

However they did have this one proper record, in Abbey Road, and often played it. Or at least Ted did (Gill seldom put on any record, unless she was doing exercises). Songs like Octopus’s Garden and Maxwell’s Silver Hammer were vital to our childhoods. So was Come Together, which McDonald extols, though as a kid (and even now) I found it quite dark, even scary. In any case, Abbey Road is my link to that period, conjuring images of Jonny Landau with his beard, his chums and his dates; Lindsay and Philippa with their books and Frisbees; Marna and her heavy-smoking husband, who actually hung out with the Pythons; Bernard Kops, the playwright, pulling funny faces in the playground at George Elliot; and our teacher at Fitzjohn’s Primary, Sandy Brownjohn, playing Beatles songs on her guitar and telling the class, ‘This is real music, not like the stuff you listen to’ (by which she meant Abba and Slade and Paper Lace.)

Picture us bumping along Finchley Road in the old Saab as Ted bursts into the opening lines of You Never Give Me your Money – before quickly fading into the rehearsal of a good joke, its punchline not quite audible, as we kids jostle in the back.

MacDonald identifies Revolver and Sergeant Pepper as the peak of the Beatles’ creativity. He describes an amazing scene: the Beatles blasting out Sergeant Pepper on a record player, early one morning in West London, just after they made it in 1967. He notes the convulsion that album caused. Some commentator at the time called it “a key moment in western civilization”. The Beatles and the Sixties were both cause and effect. Their ability to tap the spirit of The Sixties had many folks feeling that “they knew” – that the Beatles were holy men who could foresee everything.

It helps to understand that the Beatles – especially Lennon – were heavily into LSD by the mid-Sixties. They’d graduated from booze and speed to cannabis (their first joint rolled by Bob Dylan) before being swept away on the free-your-mind zeitgeist. MacDonald does not exult the LSD and he emphasises how close Lennon came to going nuts.

As he goes through the songs, one by one, which is the structure of this book, MacDonald devotes extra pages to I saw her standing there (Lennon/McCartney); Rock and Roll Music (Berry); Here, There and Everywhere (McCartney); She Said She Said (Lennon); A Day In The Life (Lennon/McCartney); I am the Walrus (Lennon); and Revolution 9 (Lennon). But those are just the ones that stick in my mind. As I heard Jarvis Cocker saying on the radio, the Beatles wrote so many great songs and so few duds.

Of all the Beatle moods – amorous, whimsical, trippy etc. – the one I like best is the rock ‘n’ roll mood. That feels like the essence of the band: songs like Twist and Shout or Back in the USSR. Here’s a playground memory from 1975: two of my classmates, Lawrence Hopkinson and Andrew Hall, are dancing on a bench, belting out Beatles songs (very well) as a group of girls surround them and scream like true fans (very well). I’m admiring from the sidelines, I’d like to be up there.

Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!

meaning to read this book for 46 years and now here I am reading it and falling asleep.

meaning to read this book for 46 years and now here I am reading it and falling asleep. This book appeared in a review by Lady Elaine Murphy of the House of Lords. She’d loved it. She called it “not a series of academic reviews but more the experience and wisdom gleaned during successful careers”. To me that sounded very cool. I was looking forward to some old shrinks reminiscing – bragging a bit of course, but also spilling the beans, admitting perhaps, with a touch of personal regret, to psychiatry’s many delusions and dead ends.

This book appeared in a review by Lady Elaine Murphy of the House of Lords. She’d loved it. She called it “not a series of academic reviews but more the experience and wisdom gleaned during successful careers”. To me that sounded very cool. I was looking forward to some old shrinks reminiscing – bragging a bit of course, but also spilling the beans, admitting perhaps, with a touch of personal regret, to psychiatry’s many delusions and dead ends. I came across Neil Postman at my cousin Jeremy’s flat in Johannesburg. I was living there in 1996. Postman’s “Amusing Ourselves to Death” was one of Jem’s favourite books – so I read it too. Jem would often use the title, with a twinkle, as a catchphrase for Johannesburg’s nightlife.

I came across Neil Postman at my cousin Jeremy’s flat in Johannesburg. I was living there in 1996. Postman’s “Amusing Ourselves to Death” was one of Jem’s favourite books – so I read it too. Jem would often use the title, with a twinkle, as a catchphrase for Johannesburg’s nightlife. Horrid Henry was Alice’s school reading book for the week. She and I had just started reading Roald Dahl’s BFG together, so we alternated between the two: she read then I read. Nice.

Horrid Henry was Alice’s school reading book for the week. She and I had just started reading Roald Dahl’s BFG together, so we alternated between the two: she read then I read. Nice. I’ve been looking for a book about the American civil war for ages, not finding one, and then this came along – an off-beat-sounding piece of fiction about a woman who disguises herself as a man – and goes off to fight. It was brilliant.

I’ve been looking for a book about the American civil war for ages, not finding one, and then this came along – an off-beat-sounding piece of fiction about a woman who disguises herself as a man – and goes off to fight. It was brilliant. Juiceboxxx is talking to his audience. “What we’re gonna do right now,” he says, “is we’re gonna go to that place called the next level. How many of you motherfuckers know about that? That next level…that’s what your fuckin’ parents warned you about. That’s what your teachers warned you about. That’s what your local city alderman warned you about! They said, ‘Hey man, don’t go to that next level, ‘cuz if you go to that next level, you’re never gonna come back!’”

Juiceboxxx is talking to his audience. “What we’re gonna do right now,” he says, “is we’re gonna go to that place called the next level. How many of you motherfuckers know about that? That next level…that’s what your fuckin’ parents warned you about. That’s what your teachers warned you about. That’s what your local city alderman warned you about! They said, ‘Hey man, don’t go to that next level, ‘cuz if you go to that next level, you’re never gonna come back!’” This is a book that people mention in connection with the American Civil War. Pat Turner was the first and his friend Tom the Artist was the second. I was coming down from Battle Cry of Freedom – and this was in a sense the novelistic version of that work of history.

This is a book that people mention in connection with the American Civil War. Pat Turner was the first and his friend Tom the Artist was the second. I was coming down from Battle Cry of Freedom – and this was in a sense the novelistic version of that work of history. What do people talk about when they talk about Karl Ove Knausgaard?

What do people talk about when they talk about Karl Ove Knausgaard?