Helen Garner

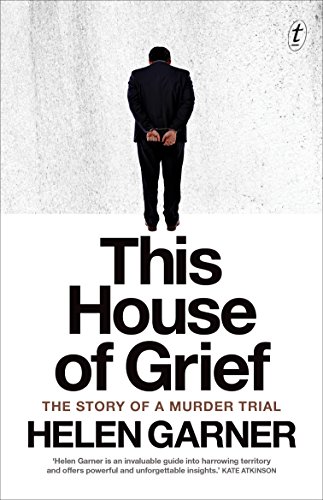

I’d already read a novel by Helen Garner, The Spare Room, which was excellent, so I was interested also to read this non-fiction book, The House of Grief, about a criminal trial that took place in Melbourne, Australia.

I’d already read a novel by Helen Garner, The Spare Room, which was excellent, so I was interested also to read this non-fiction book, The House of Grief, about a criminal trial that took place in Melbourne, Australia.

Garner, a Melbourne local, attended the trial and wrote about it. A recently divorced man had driven his car into a dam – killing his three young sons. The man survived. He claimed to have lost consciousness at the wheel after suffering a coughing fit. The trial was a big deal in Australia. It lasted many weeks and two years later was heard again at the Court of Appeals.

But the man was convicted of murder.

Garner never explains why she attended the trial. All she says is that like everybody else in Melbourne she was shocked by the news of what had happened. ‘Oh Lord, let this be an accident,’ she thinks. That is the emotion that carries us through, but it always seems an unlikely verdict. More likely it was the man’s revenge against the ex-wife who’d thrown him out – a kind of attempted homicide-suicide in which the suicide bit was a failure.

Garner describes the barristers and the witnesses, and the moods of the courtroom, with infectious curiosity. But one soon grasps the tedium of a long trial: the misery of days and days of technical details. The jurors would love to get back to their own lives. So would the judge, it often seems. But Garner never asks the question that’s hanging in the air: Is the whole production worth it? The barristers are so nasty as they twist the story, attack the characters of obviously decent people, and try to sway the emotions of the jury. If this is justice, it seems twisted.

Garner’s writing is never tedious. She sure is an interesting writer. Nonetheless it is strange that she never bothers to give an alibi for all her weeks in the courtroom. She could easily say that a newspaper had dispatched her. But she doesn’t. The reader is the judge of that.

Indeed Garner’s position is quite weird. She heads to the trial with an old friend whom she describes as follows: “Her hair was dyed a defiant red, but she had that racked look, hollow with sadness. We were women in our sixties. Each of us had found it in herself to endure – but also to inflict – the pain and humiliation of divorce.” She soon acquires a more uplifting companion, a 16-year-old girl on some kind of gap year, extremely sophisticated and precocious, in whom she takes great delight. The two of them, the old hack and the sparkling novice, are always heading to the coffee stand, mingling with the witnesses, and sharing quick, breathless opinions. There’s a kind of romance in the air. Garner’s other contacts are lawyers and journalists – old Melbourne chums. She fawns to some, snipes at others, but generally she is enamoured with the rhythms of the courtroom.

There’s something fascinating about Garner’s mix of ruthlessness and vanity – and in the simple fact that she’s a writer. I wasn’t at all surprised either when she mentioned Janet Malcom’s The Journalist and the Murderer. Garner and Malcom have some similarities. I’ve read several of Malcom’s books, including one about Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, and another about psychoanalysis in New York, and they are always brilliant. They are also demolition jobs – in the end really high-class tittle-tattle.

The other person Garner began to resemble, in the murkiness of my mind, was a child psychiatrist – I’ll call her Dr. S. – for whom I was once a trainee. This was in 2001 at a time of personal stress. At my interview for the job, to which I’d cycled across town in an old shirt and an unfocussed mood, they’d asked me the simple question, ‘Why do you want to be a child psychiatrist?’ and I’d been flummoxed. Nonetheless they gave me the job – on a kind of trial basis – and that sense of being on trial set the tone.

Now this Dr. S. was a renowned child psychiatrist who lived and breathed her chosen discipline. She was a tough old lady. Yet her feelings were easily hurt. Her special interest was court work. Like Helen Garner she loved the aura of the courtroom. Like Garner too, she loved to take young women under her wing. She must have wanted a trainee who admired her, who shared her enthusiasm for the work – someone with all the right intuitions. That wasn’t me. No, way! I was grumpy. I was bogged down with not knowing anything, with babysitting my nieces for long stints every weekend, with cycling miles and miles round London, with a crazy girlfriend (temporarily) and with smoking weed in a special pipe. About child psychiatry I was confused and skeptical. Dr S. and I disliked each other from the outset and had a year of bust-ups. At one point I even handed in a resignation letter.

As I read This House of Grief, I found myself running a kind of kangaroo court for Helen Garner, in which I threw in her guilt-by-association with Dr S. This, I hasten to admit, is an unfair and emotional way to respond to literature. And yet there it is! The author is to some extent on trial and all kinds of ridiculous half-baked evidence will be be thrown before the jury.

One day in September, during my annus horribilis with Dr S., an amazing thing happened. I was alone in the department, working on a pile of reports, when the secretary, a young, English, normally phlegmatic woman knocked on the door. Her face was ash-white. ‘Have you heard the news?’ she asked. No, I hadn’t. ‘America is under terrorist attack,’ she said. ‘They’re bombing the American cities.’ Now don’t ask me why – maybe it was the heat of the moment – but what I heard was this: ‘America is under a nuclear attack. They’re bombing the American cities.’ We walked to her office to listen to the radio. Magic FM was playing ‘The Long and Winding Road’ – the only Beatles song it ever played. We waited. I was calm. I was ready for the very, very worst. Eventually we learned that a couple of airliners had flown into the twin towers.

I was left with my relief that America had not been nuked. I went back to my office to complete my reports. Then I cycled home in a mood of tremendous elation. Instead of 3 million dead and 30 million seriously irradiated – not to mention the destruction of Western civilisation and everything that I loved and believed in – there was the relatively trivial matter of 2996 people killed and a tiny bit of collapsed infrastructure. Forgive me but I was in a damn good mood. And yet I quickly learned to (mostly) keep that mood to myself.

I’ve just looked up some figures in the archives. In 2001 in the USA there were 42,000 road traffic fatalities, 11,000 firearm homicides and 22,000 firearm suicides. But the Twin Towers was different, right? The attacks were pinned on Al-Qaeda. Afghanistan was attacked in revenge. Soon afterwards Iraq was attacked in revenge. (Everyone knew Iraq had no connection.) And less serious thinking went into that act of retribution than into the murder trial of one man in Melbourne.

Very interesting!

Loved the spine-chilling last line and the parallel you draw between writing and being on trial.

Sounds painful though. Makes the act of writing very stressful …

In any case, you have got through this trial with flying colours.

Does that make you innocent of writing badly or guilty of writing extremely well?

GUILTY as charged!

LikeLike

Thanks Sasha. I accept the guilty verdict and am willing to do my porridge. Peace and freedom to you!

LikeLike