Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer

It’s the first week of June 2016: The week Muhammad Ali dies. I avoid the newspapers, the television, all the tributes and obituaries as best I can. But I notice a copy of Mailer’s The Fight on my shelf and pull it out.

On the day of the news, a question from my partner Anna: ‘But what did he actually do, apart from being a good boxer?’ Wow! Think carefully before you answer! ‘Boxing was the least of it,’ I say. ‘And he was the greatest boxer.’

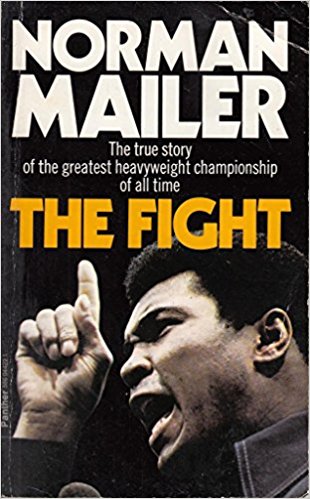

I might have advised her to read The Fight, a book that examines how far Ali transcended his sport. My copy is a tiny little paperback (published in 1977), with a great picture of Ali on the cover – not boxing but lecturing, with his index finger pointing skyward. The book is about the famous Ali-Foreman fight in 1974 – the Rumble in the Jungle – a fight that took place in Zaire. Mailer was one of many journalists and musicians who were there for the preceding weeks.

Ali’s career was in four phases. The first was from age 12, when he took up the sport, to age 25, when he was banned from boxing in the United States. By the end of this phase he was world heavyweight champion: supreme and unbeatable. The second phase, lasting over three years, was his exile from the ring, when he was active as a Civil Rights leader. The third phase was his comeback (1971-1974), which included titanic bouts against Ken Norton, Joe Frazier and George Foreman, from whom he regained the heavyweight crown. During the last phase he fought a lot, mostly won – and got badly hurt.

I first read The Fight as a teenager, along with other Ali books. I am King was a splendid photo-biography, but the one I really fell for was Sting Like a Bee by Jose Torres. The thing about that book was that the author was a boxer – Torres was an ex-light heavyweight champ from Puerto Rico. The book covers the period when Ali was returning from his exile – bigger, slower, no longer able to dance all night. Torres is at ringside, trying to figure out Ali’s responses to that loss.

Torres wrote Sting Like a Bee in the Catskill Mountains in the summer of 1972 and his neighbour that summer was Norman Mailer, who seems to have taken a lively interest in the act of creation down the road. Mailer wrote the fascinating preface to Sting Like a Bee.

However The Fight itself is not easy on a teenager. It does have a story – the two months in Kinshasa building up to the bout – but it’s a book of ideas and metaphysics. Some have called it an ego trip – all about Norman Mailer – but that seems a dated criticism. Somehow Mailer’s writing has to absorb and reflect the brilliance of Ali’s personality. It does.

Take this in a chapter called Our Black Kissinger:

“He could not, however, stay away from his mission. ‘Nobody is ready to know what I’m up to,’ he said. ‘People in America just find it hard to take a fighter seriously. They don’t know that I’m using boxing for the sake of getting over certain points you couldn’t get over without it. Being a fighter enables me to attain certain ends. I’m not doing this,’ he muttered at last, ‘for the glory of fighting, but to change a lot of things.’

It was clear what Ali was saying. One had only to open to the possibility that Ali had a large mind rather than a repetitive mind and was ready for the oncoming chaos, ready for the volcanic disruptions that would boil through the world in the coming years of pollution, malfunction and economic disaster. Who knew what camps the world would yet see? Here was this tall pale Negro from Louisville, born to be some modern species of flunky to some bourbon-minted redolent white voice, and instead he was living with a vision of himself as a world leader, president not of America or even of a United Africa, but leader of half the Western world, leader doubtless of future Black and Arab republics. Had Muhammad Mobutu Napoleon Ali come for an instant face to face with the differences between Islam and Bantu?”

My sister Nicki calls from Philadelphia, down the road from Ali’s old training camp in the Pennsylvanian mountains. ‘Sad about Ali,’ she says. ‘I’ve been watching the coverage.’ We talk about Ali.

I say, ‘Yeah. If only I had some of what he had!’

And yet the phrase – ‘If only I had some of what he had’ – is one I’ve nicked from my best friend, David Rubin. Ever since I met David, age 12, Muhammad Ali has been a kind of touchstone between us.

And David is one person who does have lots of Ali’s spirit. David’s got the quality of universality. You could drop him in Timbuktu or Ulan Bator (or Kinshasa for that matter) and he’d soon have a bunch of friends.

There’s a movie about the Ali-Foreman fight called When We Were Kings in which Norman Mailer and George Plimpton are among the talking heads. The most amazing bit of the film – enhanced by the very amazement of Plimpton and Mailer – is after the fight when Ali heads onto the early morning streets of Kinshasa to meet his people. The footage is astonishing. It’s not just his hugging children – it’s the tender way he lifts them up. It’s the way people responded to him. Mailer is in raptures at this point: ‘My God! On top of it all he’s a politician.’

At work there’s this black guy, Kevin, exactly my age, an education welfare officer, relaxed and easy to like. He’s a sports fan, a Leicester City supporter, and his team has just won the league. (They started the season at 5000 to 1, so it’s a major turn-up for the books.) After Ali dies we reminisce. We were both aged 10 when Ali fought Foreman. We both revelled in Ali’s fights – in all the talking and joking and teaching that went with them. ‘One thing I can’t understand,’ says Kevin, ‘is all the young guys at the gym – all their interest in Ali. They weren’t even born when he was fighting.’ I know just what he means: Ali was mine, yours, ours. And yet like the Big Bang, Muhammad Ali will reverberate and his feats will be re-told.

Mailer was 51 years old in Kinshasa, the same age I am now, he was playing, inventing, exploring the limits of his genius. How I wish I had a bit of that. Oh, to have a large and not a repetitive mind!

Can you say the last sentence again?

LikeLike

Look, at the risk of repeating myself, try to keep the mind large and open, or at least during office hours (8am – 5pm) and good luck with all your endeavours.

LikeLike